White Stork on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The white stork (''Ciconia ciconia'') is a large

There are two

There are two

The white stork is a large bird. It has a length of , and a standing height of . The wingspan is and its weight is . Like all storks, it has long legs, a long neck and a long straight pointed

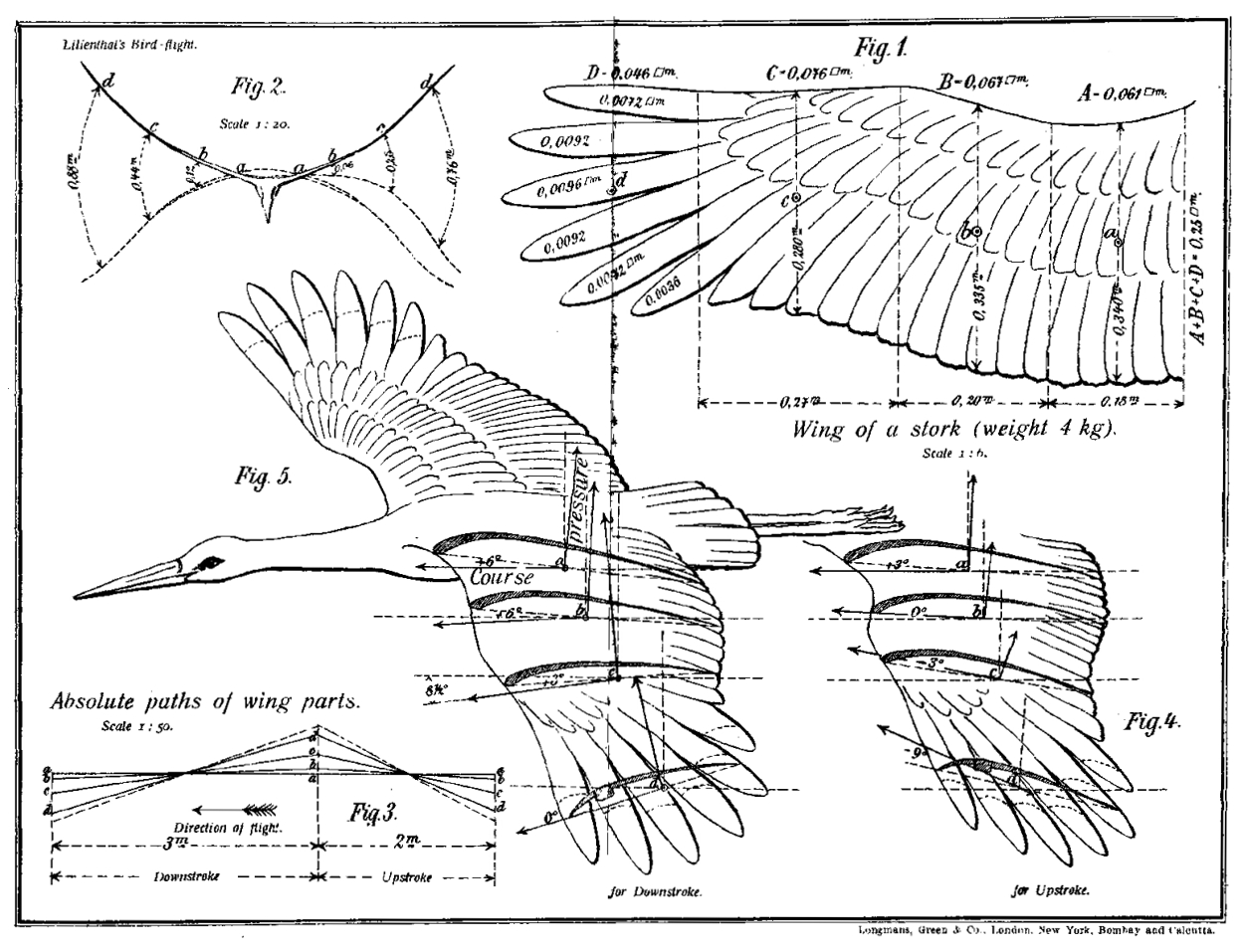

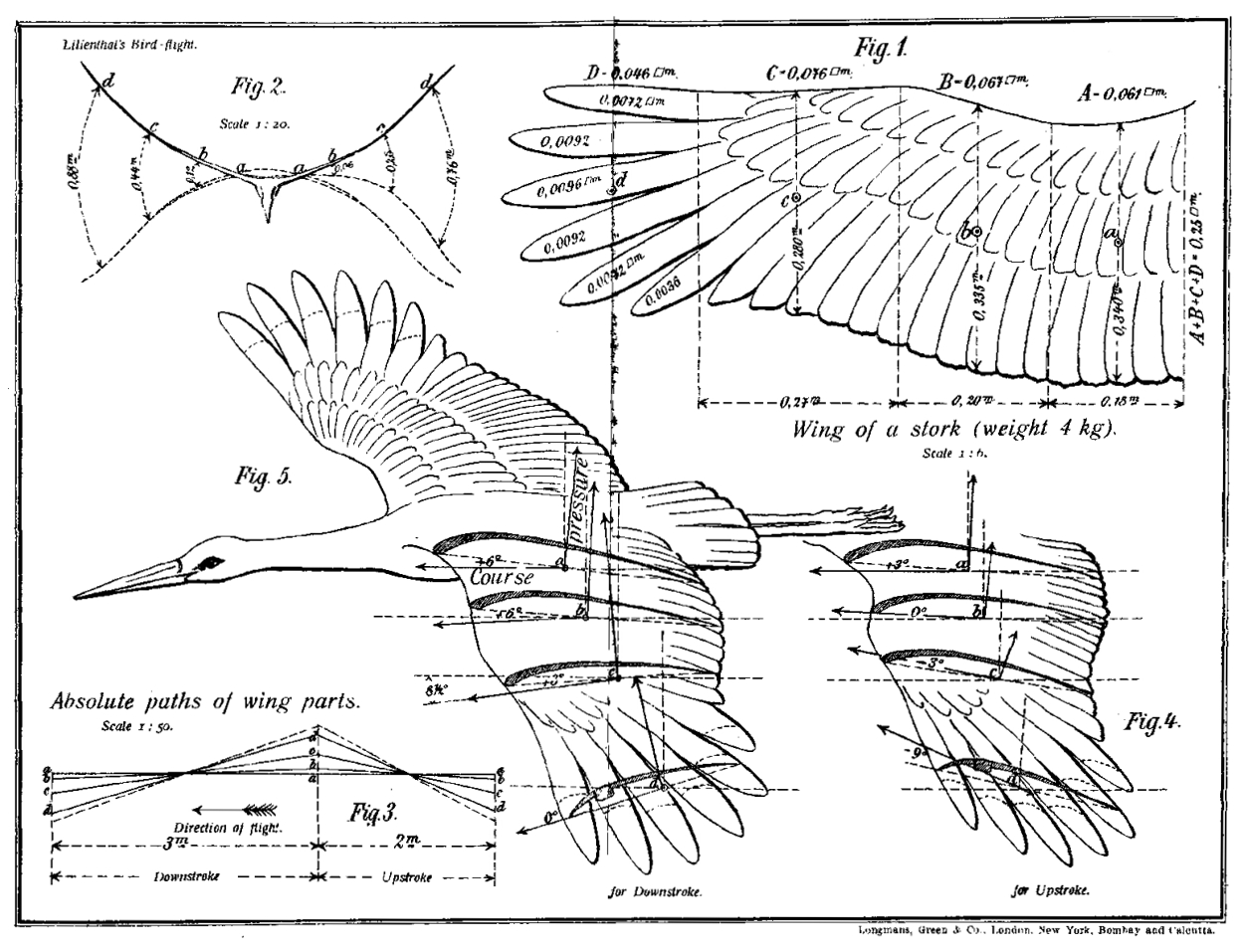

The white stork is a large bird. It has a length of , and a standing height of . The wingspan is and its weight is . Like all storks, it has long legs, a long neck and a long straight pointed  As with other storks, the wings are long and broad enabling the bird to soar. In flapping

As with other storks, the wings are long and broad enabling the bird to soar. In flapping  Upon hatching, the young white stork is partly covered with short, sparse, whitish

Upon hatching, the young white stork is partly covered with short, sparse, whitish

The

The

Systematic research into migration of the white stork began with

Systematic research into migration of the white stork began with

To avoid a long sea crossing over the Mediterranean, birds from central Europe either follow an eastern migration route by crossing the Bosphorus in Turkey, traversing the

To avoid a long sea crossing over the Mediterranean, birds from central Europe either follow an eastern migration route by crossing the Bosphorus in Turkey, traversing the

White storks rely on the uplift of air

White storks rely on the uplift of air

The white stork is a

The white stork is a

White stork (Ciconia ciconia) in flight carrying twig.jpg, carrying twig to nest

White stork (Ciconia ciconia) in flight with transmitter.jpg, bird with transmitter carrying plastic to nest

White stork (Ciconia ciconia) nest.jpg, on nest in Spain

A white stork's droppings, containing faeces and

Several bird species often nest within the large nests of the white stork. Regular occupants are

Several bird species often nest within the large nests of the white stork. Regular occupants are  The temperature and weather around the time of hatching in spring is important; cool temperatures and wet weather increase chick mortality and reduce breeding success rates. Somewhat unexpectedly, studies have found that later-hatching chicks which successfully reach adulthood produce more chicks than do their earlier-hatching nestmates. The body weight of the chicks increases rapidly in the first few weeks and reaches a plateau of about in 45 days. The length of the beak increases linearly for about 50 days. Young birds are fed with earthworms and insects, which are regurgitated by the parents onto the floor of the nest. Older chicks reach into the mouths of parents to obtain food. Chicks fledge 58 to 64 days after hatching.

White storks generally begin breeding when about four years old, although the age of first breeding has been recorded as early as two years and as late as seven years. The oldest known wild white stork lived for 39 years after being ringed in Switzerland, while captive birds have lived for more than 35 years.

The temperature and weather around the time of hatching in spring is important; cool temperatures and wet weather increase chick mortality and reduce breeding success rates. Somewhat unexpectedly, studies have found that later-hatching chicks which successfully reach adulthood produce more chicks than do their earlier-hatching nestmates. The body weight of the chicks increases rapidly in the first few weeks and reaches a plateau of about in 45 days. The length of the beak increases linearly for about 50 days. Young birds are fed with earthworms and insects, which are regurgitated by the parents onto the floor of the nest. Older chicks reach into the mouths of parents to obtain food. Chicks fledge 58 to 64 days after hatching.

White storks generally begin breeding when about four years old, although the age of first breeding has been recorded as early as two years and as late as seven years. The oldest known wild white stork lived for 39 years after being ringed in Switzerland, while captive birds have lived for more than 35 years.

Birds returning to Latvia during spring have been shown to locate their prey, moor frogs ('' Rana arvalis''), by homing in on the mating calls produced by aggregations of male frogs.

The diet of non-breeding birds is similar to that of breeding birds, but food items are more often taken from dry areas. White storks wintering in western India have been observed to follow

Birds returning to Latvia during spring have been shown to locate their prey, moor frogs ('' Rana arvalis''), by homing in on the mating calls produced by aggregations of male frogs.

The diet of non-breeding birds is similar to that of breeding birds, but food items are more often taken from dry areas. White storks wintering in western India have been observed to follow

The white stork's decline due to

The white stork's decline due to  A large population of white storks breeds in central (Poland, Ukraine and Germany) and southern Europe (Spain and Turkey). In a 2004/05 census, there were 52,500 pairs in

A large population of white storks breeds in central (Poland, Ukraine and Germany) and southern Europe (Spain and Turkey). In a 2004/05 census, there were 52,500 pairs in  In the early 1980s, the population had fallen to fewer than nine pairs in the entire upper

In the early 1980s, the population had fallen to fewer than nine pairs in the entire upper

Due to its large size, predation on vermin, and nesting behaviour close to human settlements and on rooftops, the white stork has an imposing presence that has influenced human culture and folklore. The

Due to its large size, predation on vermin, and nesting behaviour close to human settlements and on rooftops, the white stork has an imposing presence that has influenced human culture and folklore. The  Storks have little fear of humans if not disturbed, and often nest on buildings in Europe. In Germany, the presence of a nest on a house was believed to protect against fires. They were also protected because of the belief that their souls were human. German, Dutch and Polish households would encourage storks to nest on houses, sometimes by constructing purpose-built high platforms, to bring good luck. Across much of Central and Eastern Europe it is believed that storks bring harmony to a family on whose property they nest.

The white stork is a popular motif on

Storks have little fear of humans if not disturbed, and often nest on buildings in Europe. In Germany, the presence of a nest on a house was believed to protect against fires. They were also protected because of the belief that their souls were human. German, Dutch and Polish households would encourage storks to nest on houses, sometimes by constructing purpose-built high platforms, to bring good luck. Across much of Central and Eastern Europe it is believed that storks bring harmony to a family on whose property they nest.

The white stork is a popular motif on

According to European folklore, the stork is responsible for bringing babies to new parents. The legend is very ancient, but was popularised by a 19th-century

According to European folklore, the stork is responsible for bringing babies to new parents. The legend is very ancient, but was popularised by a 19th-century

In Slavic mythology and pagan religion, storks were thought to carry unborn

In Slavic mythology and pagan religion, storks were thought to carry unborn

Feathers of white stork (''Ciconia ciconia'')

Educational video about white stork (''Ciconia ciconia'')

{{Authority control

bird

Birds are a group of warm-blooded vertebrates constituting the class Aves (), characterised by feathers, toothless beaked jaws, the laying of hard-shelled eggs, a high metabolic rate, a four-chambered heart, and a strong yet lightweigh ...

in the stork

Storks are large, long-legged, long-necked wading birds with long, stout bills. They belong to the family called Ciconiidae, and make up the order Ciconiiformes . Ciconiiformes previously included a number of other families, such as herons an ...

family, Ciconiidae. Its plumage

Plumage ( "feather") is a layer of feathers that covers a bird and the pattern, colour, and arrangement of those feathers. The pattern and colours of plumage differ between species and subspecies and may vary with age classes. Within species, ...

is mainly white, with black on the bird's wings. Adults have long red legs and long pointed red beaks, and measure on average from beak tip to end of tail, with a wingspan. The two subspecies

In biological classification, subspecies is a rank below species, used for populations that live in different areas and vary in size, shape, or other physical characteristics (morphology), but that can successfully interbreed. Not all species ...

, which differ slightly in size, breed in Europe (north to Finland

Finland ( fi, Suomi ; sv, Finland ), officially the Republic of Finland (; ), is a Nordic country in Northern Europe. It shares land borders with Sweden to the northwest, Norway to the north, and Russia to the east, with the Gulf of B ...

), northwestern Africa, southwestern Asia

Western Asia, West Asia, or Southwest Asia, is the westernmost subregion of the larger geographical region of Asia, as defined by some academics, UN bodies and other institutions. It is almost entirely a part of the Middle East, and includes Ana ...

(east to southern Kazakhstan

Kazakhstan, officially the Republic of Kazakhstan, is a transcontinental country located mainly in Central Asia and partly in Eastern Europe. It borders Russia to the north and west, China to the east, Kyrgyzstan to the southeast, Uzbeki ...

) and southern Africa. The white stork is a long-distance migrant, wintering in Africa from tropical Sub-Saharan Africa

Sub-Saharan Africa is, geographically, the area and regions of the continent of Africa that lies south of the Sahara. These include West Africa, East Africa, Central Africa, and Southern Africa. Geopolitically, in addition to the List of sov ...

to as far south as South Africa

South Africa, officially the Republic of South Africa (RSA), is the southernmost country in Africa. It is bounded to the south by of coastline that stretch along the South Atlantic and Indian Oceans; to the north by the neighbouring countri ...

, or on the Indian subcontinent

The Indian subcontinent is a list of the physiographic regions of the world, physiographical region in United Nations geoscheme for Asia#Southern Asia, Southern Asia. It is situated on the Indian Plate, projecting southwards into the Indian O ...

. When migrating between Europe and Africa, it avoids crossing the Mediterranean Sea

The Mediterranean Sea is a sea connected to the Atlantic Ocean, surrounded by the Mediterranean Basin and almost completely enclosed by land: on the north by Western and Southern Europe and Anatolia, on the south by North Africa, and on the ea ...

and detours via the Levant

The Levant () is an approximate historical geographical term referring to a large area in the Eastern Mediterranean region of Western Asia. In its narrowest sense, which is in use today in archaeology and other cultural contexts, it is eq ...

in the east or the Strait of Gibraltar in the west, because the air thermals

A thermal column (or thermal) is a rising mass of buoyant air, a convective current in the atmosphere, that transfers heat energy vertically. Thermals are created by the uneven heating of Earth's surface from solar radiation, and are an example ...

on which it depends for soaring do not form over water.

A carnivore

A carnivore , or meat-eater (Latin, ''caro'', genitive ''carnis'', meaning meat or "flesh" and ''vorare'' meaning "to devour"), is an animal or plant whose food and energy requirements derive from animal tissues (mainly muscle, fat and other sof ...

, the white stork eats a wide range of animal prey, including insects, fish, amphibians, reptiles, small mammals and small birds. It takes most of its food from the ground, among low vegetation, and from shallow water. It is a monogamous breeder, but does not pair for life. Both members of the pair build a large stick nest, which may be used for several years. Each year the female can lay one clutch

A clutch is a mechanical device that engages and disengages power transmission, especially from a drive shaft to a driven shaft. In the simplest application, clutches connect and disconnect two rotating shafts (drive shafts or line shafts). ...

of usually four eggs, which hatch asynchronously 33–34 days after being laid. Both parents take turns incubating the eggs and both feed the young. The young leave the nest 58–64 days after hatching, and continue to be fed by the parents for a further 7–20 days.

The white stork has been rated as least concern

A least-concern species is a species that has been categorized by the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) as evaluated as not being a focus of species conservation because the specific species is still plentiful in the wild. T ...

by the International Union for Conservation of Nature

The International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN; officially International Union for Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources) is an international organization working in the field of nature conservation and sustainable use of natu ...

(IUCN). It benefited from human activities during the Middle Ages

In the history of Europe, the Middle Ages or medieval period lasted approximately from the late 5th to the late 15th centuries, similar to the post-classical period of global history. It began with the fall of the Western Roman Empire a ...

as woodland was cleared, but changes in farming methods and industrialisation saw it decline and disappear from parts of Europe in the 19th and early 20th centuries. Conservation and reintroduction programs across Europe have resulted in the white stork resuming breeding in the Netherlands, Belgium, Switzerland, Sweden and the United Kingdom. It has few natural predators, but may harbour several types of parasite; the plumage is home to chewing lice

The Mallophaga are a possibly paraphyletic section

Section, Sectioning or Sectioned may refer to:

Arts, entertainment and media

* Section (music), a complete, but not independent, musical idea

* Section (typography), a subdivision, especia ...

and feather mite

Feather mites are the members of diverse mite superfamilies:

* superorder Acariformes

** Psoroptidia

*** Analgoidea

*** Freyanoidea

*** Pterolichoidea

* superorder Parasitiformes

** Dermanyssoidea

They are ectoparasites on bird

B ...

s, while the large nests maintain a diverse range of mesostigmatic mites. This conspicuous species has given rise to many legends across its range, of which the best-known is the story of babies being brought by storks.

Taxonomy and evolution

English naturalistFrancis Willughby

Francis Willughby (sometimes spelt Willoughby, la, Franciscus Willughbeius) FRS (22 November 1635 – 3 July 1672) was an English ornithologist and ichthyologist, and an early student of linguistics and games.

He was born and raised at ...

wrote about the white stork in the 17th century, having seen a drawing sent to him by his friend and natural history enthusiast Sir Thomas Brown of Norwich. He named it ''Ciconia alba''. They noted they were occasional vagrants to England, blown there by storms. It was one of the many bird species originally described by Carl Linnaeus

Carl Linnaeus (; 23 May 1707 – 10 January 1778), also known after his ennoblement in 1761 as Carl von Linné Blunt (2004), p. 171. (), was a Swedish botanist, zoologist, taxonomist, and physician who formalised binomial nomenclature, the ...

in his landmark 1758 10th edition of ''Systema Naturae'', where it was given the binomial name of ''Ardea ciconia''. It was reclassified to (and was designated the type species

In zoological nomenclature, a type species (''species typica'') is the species name with which the name of a genus or subgenus is considered to be permanently taxonomically associated, i.e., the species that contains the biological type specimen ...

of) the new genus

Genus ( plural genera ) is a taxonomic rank used in the biological classification of extant taxon, living and fossil organisms as well as Virus classification#ICTV classification, viruses. In the hierarchy of biological classification, genus com ...

'' Ciconia'' by French zoologist

Zoology ()The pronunciation of zoology as is usually regarded as nonstandard, though it is not uncommon. is the branch of biology that studies the Animal, animal kingdom, including the anatomy, structure, embryology, evolution, Biological clas ...

Mathurin Jacques Brisson

Mathurin Jacques Brisson (; 30 April 1723 – 23 June 1806) was a French zoologist and natural philosopher.

Brisson was born at Fontenay-le-Comte. The earlier part of his life was spent in the pursuit of natural history; his published works ...

in 1760. Both the genus and specific epithet

In taxonomy, binomial nomenclature ("two-term naming system"), also called nomenclature ("two-name naming system") or binary nomenclature, is a formal system of naming species of living things by giving each a name composed of two parts, bot ...

, ''cĭcōnia'', are the Latin

Latin (, or , ) is a classical language belonging to the Italic branch of the Indo-European languages. Latin was originally a dialect spoken in the lower Tiber area (then known as Latium) around present-day Rome, but through the power of the ...

word for "stork".

subspecies

In biological classification, subspecies is a rank below species, used for populations that live in different areas and vary in size, shape, or other physical characteristics (morphology), but that can successfully interbreed. Not all species ...

:

* ''C. c. ciconia'', the nominate subspecies

In biological classification, subspecies is a rank below species, used for populations that live in different areas and vary in size, shape, or other physical characteristics (morphology), but that can successfully interbreed. Not all species ...

described by Linnaeus in 1758, breeds from Europe to northwestern Africa and westernmost Asia and in southern Africa, and winters mainly in Africa south of the Sahara Desert

, photo = Sahara real color.jpg

, photo_caption = The Sahara taken by Apollo 17 astronauts, 1972

, map =

, map_image =

, location =

, country =

, country1 =

, ...

, though some birds winter in India.

* ''C. c. asiatica'', described by Russian naturalist Nikolai Severtzov

Nikolai Alekseevich Severtzov (5 November 1827 – 8 February 1885) was a Russian explorer and naturalist.

Severtzov studied at the Moscow University and at the age of eighteen he came into contact with G. S. Karelin and took an interest i ...

in 1873, breeds in Turkestan

Turkestan, also spelled Turkistan ( fa, ترکستان, Torkestân, lit=Land of the Turks), is a historical region in Central Asia corresponding to the regions of Transoxiana and Xinjiang.

Overview

Known as Turan to the Persians, western Turke ...

and winters from Iran to India. It is slightly larger than the nominate subspecies.

The stork family contains six genera in three broad groups: the open-billed and wood storks (''Mycteria

''Mycteria'' is a genus of large tropical storks with representatives in the Americas, east Africa and southern and southeastern Asia. Two species have " ibis" in their scientific or old common names, but they are not related to these birds ...

'' and ''Anastomus

The openbill storks or openbills are two species of stork (family '' Ciconiidae'') in the genus ''Anastomus''. They are large wading birds characterized by large bills, the mandibles of which do not meet except at the tip. This feature develops ...

''), the giant storks (''Ephippiorhynchus

'' Ephippiorhynchus'' is a small genus of storks. It contains two living species only, very large birds more than 140 cm tall with a 230–270 cm wingspan. Both are mainly black and white, with huge bills. The sexes of these species are ...

'', ''Jabiru

The jabiru ( or ; ''Jabiru mycteria'') is a large stork found in the Americas from Mexico to Argentina, except west of the Andes. It sometimes wanders into the United States, usually in Texas, but has been reported as far north as Mississippi. ...

'' and ''Leptoptilos

''Leptoptilos'' is a genus of very large tropical storks, also known as the adjutant bird. The name means thin (''lepto'') feather (''ptilos''). Two species are resident breeders in southern Asia, and the marabou stork is found in Sub-Saharan A ...

'') and the "typical" storks ('' Ciconia''). The typical storks include the white stork and six other extant species, which are characterised by straight pointed beaks and mainly black and white plumage. Its closest relatives are the larger, black-billed Oriental stork

The Oriental stork (''Ciconia boyciana''; Japanese: コウノトリ ''Konotori'') is a large, white bird with black wing feathers in the stork family Ciconiidae.

Taxonomy

The species was first described by Robert Swinhoe in 1873. It is close ...

(''Ciconia boyciana'') of East Asia

East Asia is the eastern region of Asia, which is defined in both geographical and ethno-cultural terms. The modern states of East Asia include China, Japan, Mongolia, North Korea, South Korea, and Taiwan. China, North Korea, South Korea and ...

, which was formerly classified as a subspecies of the white stork, and the maguari stork

The maguari stork (''Ciconia maguari'') is a large species of stork that inhabits seasonal wetlands over much of South America, and is very similar in appearance to the white stork; albeit slightly larger.King CE. 1988. An ethological comparison ...

(''C. maguari'') of South America. Close evolutionary relationships within ''Ciconia'' are suggested by behavioural similarities and, biochemically, through analysis of both mitochondrial cytochrome ''b'' gene sequences and DNA-DNA hybridization.

A ''Ciconia'' fossil representing the distal

Standard anatomical terms of location are used to unambiguously describe the anatomy of animals, including humans. The terms, typically derived from Latin or Greek roots, describe something in its standard anatomical position. This position pro ...

end of a right humerus

The humerus (; ) is a long bone in the arm that runs from the shoulder to the elbow. It connects the scapula and the two bones of the lower arm, the radius and ulna, and consists of three sections. The humeral upper extremity consists of a roun ...

has been recovered from Miocene

The Miocene ( ) is the first geological epoch of the Neogene Period and extends from about (Ma). The Miocene was named by Scottish geologist Charles Lyell; the name comes from the Greek words (', "less") and (', "new") and means "less recen ...

beds of Rusinga Island

Rusinga Island, with an elongated shape approximately 10 miles (16 km) from end to end and 3 miles (5 km) at its widest point, lies in the eastern part of Lake Victoria at the mouth of the Winam Gulf. Part of Kenya, it is linked to Mbita ...

, Lake Victoria, Kenya. The 24–6 million year old fossil could have originated from either a white stork or a black stork

The black stork (''Ciconia nigra'') is a large bird in the stork family Ciconiidae. It was first described by Carl Linnaeus in the 10th edition of his ''Systema Naturae''. Measuring on average from beak tip to end of tail with a wingspan, th ...

(''C. nigra''), which are species of about the same size with very similar bone structures. The Middle Miocene

The Middle Miocene is a sub-epoch of the Miocene Epoch made up of two stages: the Langhian and Serravallian stages. The Middle Miocene is preceded by the Early Miocene.

The sub-epoch lasted from 15.97 ± 0.05 Ma to 11.608 ± 0.005 Ma (million y ...

beds of Maboko Island

Maboko Island is a small island lying in the Winam Gulf of Lake Victoria, in Nyanza Province of western Kenya. It is about 1.8 km long by 1 km wide. It is an important Middle Miocene paleontological site with fossiliferous deposits that were di ...

have yielded further remains.

Description

The white stork is a large bird. It has a length of , and a standing height of . The wingspan is and its weight is . Like all storks, it has long legs, a long neck and a long straight pointed

The white stork is a large bird. It has a length of , and a standing height of . The wingspan is and its weight is . Like all storks, it has long legs, a long neck and a long straight pointed beak

The beak, bill, or rostrum is an external anatomical structure found mostly in birds, but also in turtles, non-avian dinosaurs and a few mammals. A beak is used for eating, preening, manipulating objects, killing prey, fighting, probing for food ...

. The sexes are identical in appearance, except that males are larger than females on average. The plumage

Plumage ( "feather") is a layer of feathers that covers a bird and the pattern, colour, and arrangement of those feathers. The pattern and colours of plumage differ between species and subspecies and may vary with age classes. Within species, ...

is mainly white with black flight feather

Flight feathers (''Pennae volatus'') are the long, stiff, asymmetrically shaped, but symmetrically paired pennaceous feathers on the wings or tail of a bird; those on the wings are called remiges (), singular remex (), while those on the tail ...

s and wing coverts

A covert feather or tectrix on a bird is one of a set of feathers, called coverts (or ''tectrices''), which, as the name implies, cover other feathers. The coverts help to smooth airflow over the wings and tail. Ear coverts

The ear coverts are s ...

; the black is caused by the pigment melanin

Melanin (; from el, μέλας, melas, black, dark) is a broad term for a group of natural pigments found in most organisms. Eumelanin is produced through a multistage chemical process known as melanogenesis, where the oxidation of the amino ...

. The breast feathers are long and shaggy forming a ruff which is used in some courtship displays. The irises are dull brown or grey, and the peri- orbital skin is black. The adult has a bright red beak and red legs, the colouration of which is derived from carotenoids in the diet. In parts of Spain, studies have shown that the pigment is based on astaxanthin

Astaxanthin is a keto- carotenoid within a group of chemical compounds known as terpenes. Astaxanthin is a metabolite of zeaxanthin and canthaxanthin, containing both hydroxyl and ketone functional groups. It is a lipid-soluble pigment with r ...

obtained from an introduced species of crayfish (''Procambarus clarkii

''Procambarus clarkii'', known variously as the red swamp crayfish, Louisiana crawfish or mudbug, is a species of cambarid crayfish native to freshwater bodies of northern Mexico, and southern and southeastern United States, but also introduce ...

'') and the bright red beak colours show up even in nestlings, in contrast to the duller beaks of young white storks elsewhere.

flight

Flight or flying is the process by which an object moves through a space without contacting any planetary surface, either within an atmosphere (i.e. air flight or aviation) or through the vacuum of outer space (i.e. spaceflight). This can be a ...

its wingbeats are slow and regular. It flies with its neck stretched forward and with its long legs extended well beyond the end of its short tail. It walks at a slow and steady pace with its neck upstretched. In contrast, it often hunches its head between its shoulders when resting. Moulting

In biology, moulting (British English), or molting (American English), also known as sloughing, shedding, or in many invertebrates, ecdysis, is the manner in which an animal routinely casts off a part of its body (often, but not always, an outer ...

has not been extensively studied, but appears to take place throughout the year, with the primary flight feathers replaced over the breeding season.

down feather

The down of birds is a layer of fine feathers found under the tougher exterior feathers. Very young birds are clad only in down. Powder down is a specialized type of down found only in a few groups of birds. Down is a fine thermal insulator an ...

s. This early down is replaced about a week later with a denser coat of woolly white down. By three weeks, the young bird acquires black scapulars and flight feather

Flight feathers (''Pennae volatus'') are the long, stiff, asymmetrically shaped, but symmetrically paired pennaceous feathers on the wings or tail of a bird; those on the wings are called remiges (), singular remex (), while those on the tail ...

s. On hatching the chick has pinkish legs, which turn to greyish-black as it ages. Its beak is black with a brownish tip. By the time it fledge

Fledging is the stage in a flying animal's life between hatching or birth and becoming capable of flight.

This term is most frequently applied to birds, but is also used for bats. For altricial birds, those that spend more time in vulnerable c ...

s, the juvenile bird's plumage is similar to that of the adult, though its black feathers are often tinged with brown, and its beak and legs are a duller brownish-red or orange. The beak is typically orange or red with a darker tip. The bills gain the adults' red colour the following summer, although the black tips persist in some individuals. Young storks adopt adult plumage by their second summer.

Similar species

Within its range the white stork is distinctive when seen on the ground. The winter range of ''C. c. asiatica'' overlaps that of theAsian openbill

The Asian openbill or Asian openbill stork (''Anastomus oscitans'') is a large wading bird in the stork family Ciconiidae. This distinctive stork is found mainly in the Indian subcontinent and Southeast Asia. It is greyish or white with glossy ...

, which has similar plumage but a different bill shape. When seen at a distance in flight, the white stork can be confused with several other species with similar underwing patterns, such as the yellow-billed stork, great white pelican

The great white pelican (''Pelecanus onocrotalus'') also known as the eastern white pelican, rosy pelican or white pelican is a bird in the pelican family. It breeds from southeastern Europe through Asia and Africa, in swamps and shallow lakes. ...

and Egyptian vulture

The Egyptian vulture (''Neophron percnopterus''), also called the white scavenger vulture or pharaoh's chicken, is a small Old World vulture and the only member of the genus ''Neophron''. It is widely distributed from the Iberian Peninsula and ...

. The yellow-billed stork is identified by its black tail and a longer, slightly curved, yellow beak. The white stork also tends to be larger than the yellow-billed stork. The great white pelican has short legs which do not extend beyond its tail, and it flies with its neck retracted, keeping its head near to its stocky body, giving it a different flight profile. Pelicans also behave differently, soaring in orderly, synchronised flocks rather than in disorganised groups of individuals as the white stork does. The Egyptian vulture is much smaller, with a long wedge-shaped tail, shorter legs and a small yellow-tinged head on a short neck. The common crane

The common crane (''Grus grus''), also known as the Eurasian crane, is a bird of the family Gruidae, the cranes. A medium-sized species, it is the only crane commonly found in Europe besides the demoiselle crane (''Grus virgo'') and the Siberian ...

, which can also look black and white in strong light, shows longer legs and a longer neck in flight.

Distribution and habitat

nominate race

In biological classification, subspecies is a rank below species, used for populations that live in different areas and vary in size, shape, or other physical characteristics ( morphology), but that can successfully interbreed. Not all specie ...

of the white stork has a wide although disjunct summer range across Europe, clustered in the Iberian Peninsula

The Iberian Peninsula (),

**

* Aragonese and Occitan: ''Peninsula Iberica''

**

**

* french: Péninsule Ibérique

* mwl, Península Eibérica

* eu, Iberiar penintsula also known as Iberia, is a peninsula in southwestern Europe, defi ...

and North Africa in the west, and much of eastern and central Europe, with 25% of the world's population concentrated in Poland, as well as parts of western Asia

Western Asia, West Asia, or Southwest Asia, is the westernmost subregion of the larger geographical region of Asia, as defined by some academics, UN bodies and other institutions. It is almost entirely a part of the Middle East, and includes Ana ...

. The ''asiatica'' population of about 1450 birds is restricted to a region in central Asia between the Aral Sea

The Aral Sea ( ; kk, Арал теңізі, Aral teñızı; uz, Орол денгизи, Orol dengizi; kaa, Арал теңизи, Aral teńizi; russian: Аральское море, Aral'skoye more) was an endorheic basin, endorheic lake lyi ...

and Xinjiang

Xinjiang, SASM/GNC: ''Xinjang''; zh, c=, p=Xīnjiāng; formerly romanized as Sinkiang (, ), officially the Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region (XUAR), is an autonomous region of the People's Republic of China (PRC), located in the northwest ...

in western China. The Xinjiang population is believed to have become extinct around 1980. Migration

Migration, migratory, or migrate may refer to: Human migration

* Human migration, physical movement by humans from one region to another

** International migration, when peoples cross state boundaries and stay in the host state for some minimum le ...

routes extend the range of this species into many parts of Africa and India. Some populations adhere to the eastern migration route, which passes across Israel into eastern and central Africa.

A few records of breeding from South Africa have been known since 1933 at Calitzdorp

Calitzdorp is a town on the Western side of the Little or Klein Karoo in the Western Cape Province

The Western Cape is a province of South Africa, situated on the south-western coast of the country. It is the fourth largest of the nine provi ...

, and about 10 birds have been known to breed since the 1990s around Bredasdorp

Bredasdorp is a town in the Southern Overberg region of the Western Cape, South Africa, and the main economic and service hub of that region. It lies on the northern edge of the Agulhas Plain, about south-east of Cape Town and north of Cape Agu ...

. A small population of white storks winters in India and is thought to derive principally from the ''C. c. asiatica'' population as flocks of up to 200 birds have been observed on spring migration in the early 1900s through the Kurram Valley

Kurram District ( ps, کرم ولسوالۍ, ur, ) is a district in Kohat Division of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa province in Pakistan.The name Kurram comes from the river Kuramá ( ps, کورمه) in Pashto which itself derives from the Sanskrit name Kr ...

. However, birds ringed in Germany have been recovered in western (Bikaner

Bikaner () is a city in the northwest of the state of Rajasthan, India. It is located northwest of the state capital, Jaipur. Bikaner city is the administrative headquarters of Bikaner District and Bikaner division.

Formerly the capital of ...

) and southern (Tirunelveli

Tirunelveli (, ta, திருநெல்வேலி, translit=Tirunelveli) also known as Nellai ( ta, நெல்லை, translit=Nellai) and historically (during British rule) as Tinnevelly, is a major city in the Indian state of Tami ...

) India. An atypical specimen with red orbital skin, a feature of the Oriental white stork, has been recorded and further study of the Indian population is required. North of the breeding range, it is a passage migrant or vagrant

Vagrancy is the condition of homelessness without regular employment or income. Vagrants (also known as bums, vagabonds, rogues, tramps or drifters) usually live in poverty and support themselves by begging, scavenging, petty theft, temporar ...

in Finland, Iceland, Ireland, Norway and Sweden, and west to the Azores

)

, motto =( en, "Rather die free than subjected in peace")

, anthem= ( en, "Anthem of the Azores")

, image_map=Locator_map_of_Azores_in_EU.svg

, map_alt=Location of the Azores within the European Union

, map_caption=Location of the Azores wi ...

and Madeira

)

, anthem = ( en, "Anthem of the Autonomous Region of Madeira")

, song_type = Regional anthem

, image_map=EU-Portugal_with_Madeira_circled.svg

, map_alt=Location of Madeira

, map_caption=Location of Madeira

, subdivision_type=Sovereign st ...

. Despite their geographical proximity, in Finland the species is rare, while in Estonia there are an estimated 5,000 breeding pairs. In recent years, the range has expanded into western Russia.

The white stork's preferred feeding grounds are grassy meadows, farmland and shallow wetlands. It avoids areas overgrown with tall grass and shrubs. In the Chernobyl

Chernobyl ( , ; russian: Чернобыль, ) or Chornobyl ( uk, Чорнобиль, ) is a partially abandoned city in the Chernobyl Exclusion Zone, situated in the Vyshhorod Raion of northern Kyiv Oblast, Ukraine. Chernobyl is about no ...

area of northern Ukraine, white stork populations declined after the 1986 nuclear accident there as farmland was succeeded by tall grass shrubs. In parts of Poland, poor natural foraging grounds have forced birds to seek food at rubbish dump

A landfill site, also known as a tip, dump, rubbish dump, garbage dump, or dumping ground, is a site for the disposal of waste materials. Landfill is the oldest and most common form of waste disposal, although the systematic burial of the waste ...

s since 1999. White storks have also been reported foraging in rubbish dumps in the Middle East, North Africa and South Africa.

The white stork breeds in greater numbers in areas with open grasslands, particularly grassy areas which are wet or periodically flooded, and less in areas with taller vegetation cover such as forest and shrubland. They make use of grasslands, wetlands, and farmland on the wintering grounds in Africa. White storks were probably aided by human activities during the Middle Ages

In the history of Europe, the Middle Ages or medieval period lasted approximately from the late 5th to the late 15th centuries, similar to the post-classical period of global history. It began with the fall of the Western Roman Empire a ...

as woodland was cleared and new pastures and farmland were created, and they were found across much of Europe, breeding as far north as Sweden. The population in Sweden is thought to have established in the 16th century after forests were cut down for agriculture. About 5000 pairs were estimated to breed in the 18th century which declined subsequently. The first accurate census in 1917 found 25 pairs and the last pair failed to breed around 1955. The white stork has been a rare visitor to the British Isles

The British Isles are a group of islands in the North Atlantic Ocean off the north-western coast of continental Europe, consisting of the islands of Great Britain, Ireland, the Isle of Man, the Inner and Outer Hebrides, the Northern Isles, ...

, with about 20 birds seen in Britain every year, and prior to 2020 there were no records of nesting since a pair nested atop St Giles High Kirk in Edinburgh

Edinburgh ( ; gd, Dùn Èideann ) is the capital city of Scotland and one of its 32 Council areas of Scotland, council areas. Historically part of the county of Midlothian (interchangeably Edinburghshire before 1921), it is located in Lothian ...

, Scotland in 1416. In 2020, a pair bred in the United Kingdom for the first time in over 600 years, as part of an re-introduction initiative in West Sussex

West Sussex is a county in South East England on the English Channel coast. The ceremonial county comprises the shire districts of Adur, Arun, Chichester, Horsham, and Mid Sussex, and the boroughs of Crawley and Worthing. Covering an ar ...

called the White Stork Project.

A decline in population began in the 19th century due to industrialisation

Industrialisation ( alternatively spelled industrialization) is the period of social and economic change that transforms a human group from an agrarian society into an industrial society. This involves an extensive re-organisation of an econo ...

and changes in agricultural methods. White storks no longer nest in many countries, and the current strongholds of the western population are in Portugal, Spain, Ukraine and Poland. In the Iberian Peninsula, populations are concentrated in the southwest, and have also declined due to agricultural practices. A study published in 2005 found that the Podhale

Podhale (literally "below the mountain pastures") is Poland's southernmost region, sometimes referred to as the "Polish Highlands". The Podhale is located in the foothills of the Tatra range of the Carpathian mountains. It is the most famous ...

region in the uplands of southern Poland had seen an influx of white storks, which first bred there in 1931 and have nested at progressively higher altitudes since, reaching 890 m (3000 ft) in 1999. The authors proposed that this was related to climate warming

In common usage, climate change describes global warming—the ongoing increase in global average temperature—and its effects on Earth's climate system. Climate change in a broader sense also includes previous long-term changes to E ...

and the influx of other animals and plants to higher altitudes. White storks arriving in Poznań province (Greater Poland Voivodeship

Greater Poland Voivodeship ( pl, Województwo wielkopolskie; ), also known as Wielkopolska Voivodeship, Wielkopolska Province, or Greater Poland Province, is a voivodeship, or province, in west-central Poland. It was created on 1 January 1999 ...

) in western Poland in spring to breed did so some 10 days earlier in the last twenty years of the 20th century than at the end of the 19th century.

Migration

Systematic research into migration of the white stork began with

Systematic research into migration of the white stork began with German

German(s) may refer to:

* Germany (of or related to)

** Germania (historical use)

* Germans, citizens of Germany, people of German ancestry, or native speakers of the German language

** For citizens of Germany, see also German nationality law

**Ge ...

ornithologist Johannes Thienemann

Johannes Thienemann (12 November 1863 – 12 April 1938) was a German ornithology, ornithologist and pastor who established the Rossitten Bird Observatory, the world's first dedicated bird ringing station where he conducted research and populariz ...

who commenced bird ringing studies in 1906 at the Rossitten Bird Observatory

The Rossitten Bird Observatory (''Vogelwarte Rossitten'' in German) was the world's first ornithological observatory. It was sited at Rossitten, East Prussia (now Rybachy, Kaliningrad Oblast, Russia), on the Curonian Spit on the south-eastern c ...

, on the Curonian Spit

The Curonian (Courish) Spit ( lt, Kuršių nerija; russian: Ку́ршская коса́ (Kurshskaya kosa); german: Kurische Nehrung, ; lv, Kuršu kāpas) is a long, thin, curved sand-dune spit that separates the Curonian Lagoon from the Balti ...

in what was then East Prussia

East Prussia ; german: Ostpreißen, label=Low Prussian; pl, Prusy Wschodnie; lt, Rytų Prūsija was a province of the Kingdom of Prussia from 1773 to 1829 and again from 1878 (with the Kingdom itself being part of the German Empire from 187 ...

. Although not many storks passed through Rossitten itself, the observatory coordinated the large-scale ringing of the species throughout Germany and elsewhere in Europe. Between 1906 and the Second World War

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposin ...

about 100,000, mainly juvenile, white storks were ringed, with over 2,000 long-distance recoveries of birds wearing Rossitten rings reported between 1908 and 1954.

Routes

White storks fly south from their summer breeding grounds in Europe in August and September, heading for Africa. There, they spend the winter insavannah

A savanna or savannah is a mixed woodland-grassland (i.e. grassy woodland) ecosystem characterised by the trees being sufficiently widely spaced so that the Canopy (forest), canopy does not close. The open canopy allows sufficient light to rea ...

from Kenya and Uganda south to the Cape Province

The Province of the Cape of Good Hope ( af, Provinsie Kaap die Goeie Hoop), commonly referred to as the Cape Province ( af, Kaapprovinsie) and colloquially as The Cape ( af, Die Kaap), was a province in the Union of South Africa and subsequen ...

of South Africa. In these areas, they congregate in large flocks which may exceed a thousand individuals. Some diverge westwards into western Sudan and Chad, and may reach Nigeria.

In spring, the birds return north; they are recorded from Sudan and Egypt from February to April. They arrive back in Europe around late March and April, after an average journey of 49 days. By comparison, the autumn journey is completed in about 26 days. Tailwind

A tailwind is a wind that blows in the direction of travel of an object, while a headwind blows against the direction of travel. A tailwind increases the object's speed and reduces the time required to reach its destination, while a headwind has ...

s and scarcity of food and water en route (birds fly faster over regions lacking resources) increase average speed.

To avoid a long sea crossing over the Mediterranean, birds from central Europe either follow an eastern migration route by crossing the Bosphorus in Turkey, traversing the

To avoid a long sea crossing over the Mediterranean, birds from central Europe either follow an eastern migration route by crossing the Bosphorus in Turkey, traversing the Levant

The Levant () is an approximate historical geographical term referring to a large area in the Eastern Mediterranean region of Western Asia. In its narrowest sense, which is in use today in archaeology and other cultural contexts, it is eq ...

, then bypassing the Sahara Desert

, photo = Sahara real color.jpg

, photo_caption = The Sahara taken by Apollo 17 astronauts, 1972

, map =

, map_image =

, location =

, country =

, country1 =

, ...

by following the Nile

The Nile, , Bohairic , lg, Kiira , Nobiin language, Nobiin: Áman Dawū is a major north-flowing river in northeastern Africa. It flows into the Mediterranean Sea. The Nile is the longest river in Africa and has historically been considered ...

valley southwards, or follow a western route over the Strait of Gibraltar. These migration corridors maximise help from the thermals and thus save energy.

In winter 2013–2014, white storks were observed in southern India's Mudumalai National Park

Mudumalai National Park is a national park in the Nilgiri Mountains in Tamil Nadu, south India. It covers at an elevation range of in the Nilgiri District and shares boundaries with the states of Karnataka and Kerala. A part of this area ha ...

for the first time.

The eastern route is by far the more important with 530,000 white storks using it annually, making the species the second commonest migrant there (after the European honey buzzard

The European honey buzzard (''Pernis apivorus''), also known as the pern or common pern, is a bird of prey in the family Accipitridae.

Etymology

Despite its English name, this species is more closely related to kites of the genera '' Leptodon'' a ...

). The flocks of migrating raptor

Raptor or RAPTOR may refer to:

Animals

The word "raptor" refers to several groups of bird-like dinosaurs which primarily capture and subdue/kill prey with their talons.

* Raptor (bird) or bird of prey, a bird that primarily hunts and feeds on ...

s, white storks and great white pelican

The great white pelican (''Pelecanus onocrotalus'') also known as the eastern white pelican, rosy pelican or white pelican is a bird in the pelican family. It breeds from southeastern Europe through Asia and Africa, in swamps and shallow lakes. ...

s can stretch for 200 km (125 mi). The eastern route is twice as long as the western, but storks take the same time to reach the wintering grounds by either.

Juvenile white storks set off on their first southward migration in an inherited direction but, if displaced from that bearing by weather conditions, they are unable to compensate, and may end up in a new wintering location. Adults can compensate for strong winds and adjust their direction to finish at their normal winter sites, because they are familiar with the location. For the same reason, all spring migrants, even those from displaced wintering locations, can find their way back to the traditional breeding sites. An experiment with young birds raised in captivity in Kaliningrad and released in the absence of wild storks to show them the way revealed that they appeared to have an instinct to fly south, although the scatter in direction was large.

Energetics

White storks rely on the uplift of air

White storks rely on the uplift of air thermal

A thermal column (or thermal) is a rising mass of buoyant air, a convective current in the atmosphere, that transfers heat energy vertically. Thermals are created by the uneven heating of Earth's surface from solar radiation, and are an example ...

s to soar and glide the long distances of their annual migrations between Europe and Sub-Saharan Africa

Sub-Saharan Africa is, geographically, the area and regions of the continent of Africa that lies south of the Sahara. These include West Africa, East Africa, Central Africa, and Southern Africa. Geopolitically, in addition to the List of sov ...

. For many, the shortest route would take them over the Mediterranean Sea

The Mediterranean Sea is a sea connected to the Atlantic Ocean, surrounded by the Mediterranean Basin and almost completely enclosed by land: on the north by Western and Southern Europe and Anatolia, on the south by North Africa, and on the ea ...

; however, since air thermals do not form over water, they generally detour over land to avoid the trans-Mediterranean flights that would require prolonged energetic wing flapping. It has been estimated that flapping flight metabolises 23 times more body fat than soaring flight per distance travelled. Thus, flocks spiral upwards on rising warm air until they emerge at the top, up to above the ground (though one record from Western Sudan observed an altitude of ).

Long flights over water may occasionally be undertaken. A young white stork ringed at the nest in Denmark subsequently appeared in England, where it spent some days before moving on. It was later seen flying over St Mary's, Isles of Scilly

St Mary's ( kw, Ennor, meaning ''The Mainland'') is the largest and most populous island of the Isles of Scilly, an archipelago off the southwest coast of Cornwall in England.

Description

St Mary's has an area of — 40 percent of the total la ...

, and arrived in a poor condition in Madeira

)

, anthem = ( en, "Anthem of the Autonomous Region of Madeira")

, song_type = Regional anthem

, image_map=EU-Portugal_with_Madeira_circled.svg

, map_alt=Location of Madeira

, map_caption=Location of Madeira

, subdivision_type=Sovereign st ...

three days later. That island is 500 km (320 mi) from Africa, and twice as far from the European mainland. Migration through the Middle East

The Middle East ( ar, الشرق الأوسط, ISO 233: ) is a geopolitical region commonly encompassing Arabian Peninsula, Arabia (including the Arabian Peninsula and Bahrain), Anatolia, Asia Minor (Asian part of Turkey except Hatay Pro ...

may be hampered by the ''khamsin

Khamsin, chamsin or hamsin ( ar, خمسين , meaning "fifty"), more commonly known in Egypt as khamaseen ( arz, خماسين , ), is a dry, hot, sandy local wind affecting Egypt and the Levant; similar winds, blowing in other parts of North ...

'', winds bringing gusty overcast days unsuitable for flying. In these situations, flocks of white storks sit out the adverse weather on the ground, standing and facing into the wind.

Behaviour

gregarious

Sociality is the degree to which individuals in an animal population tend to associate in social groups (gregariousness) and form cooperative societies.

Sociality is a survival response to evolutionary pressures. For example, when a mother wasp ...

bird; flocks of thousands of individuals have been recorded on migration routes and at wintering areas in Africa. Non-breeding birds gather in groups of 40 or 50 during the breeding season. The smaller dark-plumaged Abdim's stork

Abdim's stork (''Ciconia abdimii''), also known as the white-bellied stork, is a stork belonging to the family Ciconiidae. It is the smallest species of stork, feeds mostly on insects, and is found widely in open habitats in Sub-Saharan Africa a ...

is often encountered with white stork flocks in southern Africa. Breeding pair

Breeding pair is a pair of animals which cooperate over time to produce offspring with some form of a bond between the individuals.Gaston, A. J.The evolution of group territorial behavior and cooperative breeding" The American Naturalist 112.988 ...

s of white stork may gather in small groups to hunt, and colony nesting has been recorded in some areas. However, groups among white stork colonies vary widely in size and the social structure is loosely defined; young breeding storks are often restricted to peripheral nests, while older storks attain higher breeding success while occupying the better quality nests toward the centres of breeding colonies. Social structure and group cohesion is maintained by altruistic

Altruism is the principle and moral practice of concern for the welfare and/or happiness of other human beings or animals, resulting in a quality of life both material and spiritual. It is a traditional virtue in many cultures and a core asp ...

behaviours such as allopreening

Preening is a found in birds that involves the use of the beak to position feathers, interlock feather that have become separated, clean plumage, and keep ectoparasites in check. Feathers contribute significantly to a bird's insulation, waterp ...

. White storks exhibit this behaviour exclusively at the nest site. Standing birds preen the heads of sitting birds, sometimes these are parents grooming juveniles, and sometimes juveniles preen each other. Unlike most storks, it never adopts a spread-winged posture, though it is known to droop its wings (holding them away from its body with the primary feather

Flight feathers (''Pennae volatus'') are the long, stiff, asymmetrically shaped, but symmetrically paired pennaceous feathers on the wings or tail of a bird; those on the wings are called remiges (), singular remex (), while those on the tail ...

s pointing downwards) when its plumage is wet.

uric acid

Uric acid is a heterocyclic compound of carbon, nitrogen, oxygen, and hydrogen with the formula C5H4N4O3. It forms ions and salts known as urates and acid urates, such as ammonium acid urate. Uric acid is a product of the metabolic breakdown ...

, are sometimes directed onto its own legs, making them appear white. The resulting evaporation provides cooling and is termed urohidrosis

Urohidrosis (sometimes misspelled "urohydrosis") is the habit in some birds of defecating onto the scaly portions of the legs as a cooling mechanism, using evaporative cooling of the fluids. Several species of storks and New World vultures exhibi ...

. Birds that have been ringed can sometimes be affected by the accumulation of droppings around the ring leading to constriction and leg trauma. The white stork has also been noted for tool use by squeezing moss in the beak to drip water into the mouths of its chicks.

Communication

The adult white stork's main sound is noisy bill-clattering, which has been likened to distant machine gun fire. The bird makes these sounds by rapidly opening and closing its beak so that a knocking sound is made each time its beak closes. The clattering is amplified by itsthroat pouch

Gular skin (throat skin), in ornithology, is an area of featherless skin on birds that joins the lower mandible of the beak (or ''bill'') to the bird's neck. Other vertebrate taxa may have a comparable anatomical structure that is referred to as ...

, which acts as a resonator

A resonator is a device or system that exhibits resonance or resonant behavior. That is, it naturally oscillates with greater amplitude at some frequencies, called resonant frequencies, than at other frequencies. The oscillations in a resonator ...

. Used in a variety of social interactions, bill-clattering generally grows louder the longer it lasts, and takes on distinctive rhythms depending on the situation—for example, slower during copulation and briefer when given as an alarm call

In animal communication, an alarm signal is an antipredator adaptation in the form of signals emitted by social animals in response to danger. Many primates and birds have elaborate alarm calls for warning conspecifics of approaching predator ...

. The only vocal sound adult birds generate is a weak barely audible hiss; however, young birds can generate a harsh hiss, various cheeping sounds, and a cat-like mew they use to beg for food. Like the adults, young also clatter their beaks. The ''up-down display'' is used for a number of interactions with other members of the species. Here a stork quickly throws its head backwards so that its crown rests on its back before slowly bringing its head and neck forwards again, and this is repeated several times. The display is used as a greeting between birds, post coitus, and also as a threat display

Deimatic behaviour or startle display means any pattern of bluffing behaviour in an animal that lacks strong defences, such as suddenly displaying conspicuous eyespots, to scare off or momentarily distract a predator, thus giving the prey anima ...

. Breeding pairs are territorial

A territory is an area of land, sea, or space, particularly belonging or connected to a country, person, or animal.

In international politics, a territory is usually either the total area from which a state may extract power resources or a ...

over the summer, and use this display, as well as crouching forward with the tails cocked and wings extended.

Breeding and lifespan

The white stork breeds in open farmland areas with access to marshy wetlands, building a large sticknest

A nest is a structure built for certain animals to hold eggs or young. Although nests are most closely associated with birds, members of all classes of vertebrates and some invertebrates construct nests. They may be composed of organic materia ...

in trees, on buildings, or on purpose-built man-made platforms. Each nest is in depth, in diameter, and in weight. Nests are built in loose colonies. Not persecuted as it is viewed as a good omen, it often nests close to human habitation; in southern Europe, nests can be seen on churches and other buildings. The nest is typically used year after year especially by older males. The males arrive earlier in the season and choose the nests. Larger nests are associated with greater numbers of young successfully fledged, and appear to be sought after. Nest change is often related to a change in the pairing and failure to raise young the previous year, and younger birds are more likely to change nesting sites. Although a pair may be found to occupy a nest, partners may change several times during the early stages and breeding activities begin only after a stable pairing is achieved.

house sparrow

The house sparrow (''Passer domesticus'') is a bird of the sparrow family Passeridae, found in most parts of the world. It is a small bird that has a typical length of and a mass of . Females and young birds are coloured pale brown and grey, a ...

s, tree sparrow

The Eurasian tree sparrow (''Passer montanus'') is a passerine bird in the sparrow family with a rich chestnut crown and nape, and a black patch on each pure white cheek. The sexes are similarly plumaged, and young birds are a duller version o ...

s, and common starlings; less common residents include Eurasian kestrel

The common kestrel (''Falco tinnunculus'') is a bird of prey species belonging to the kestrel group of the falcon family Falconidae. It is also known as the European kestrel, Eurasian kestrel, or Old World kestrel. In the United Kingdom, where no ...

s, little owls, European roller

The European roller (''Coracias garrulus'') is the only member of the roller family of birds to breed in Europe. Its overall range extends into the Middle East, Central Asia and the Maghreb.

The European roller is found in a wide variety of hab ...

s, white wagtail

The white wagtail (''Motacilla alba'') is a small passerine bird in the family Motacillidae, which also includes pipits and longclaws. The species breeds in much of Europe and the Asian Palearctic and parts of North Africa. It has a toehold in ...

s, black redstart

The black redstart (''Phoenicurus ochruros'') is a small passerine bird in the genus ''Phoenicurus''. Like its relatives, it was formerly classed as a member of the thrush family (Turdidae), but is now known to be an Old World flycatcher (Muscic ...

s, Eurasian jackdaws, and Spanish sparrow

The Spanish sparrow or willow sparrow (''Passer hispaniolensis'') is a passerine bird of the sparrow family Passeridae. It is found in the Mediterranean region and south-west and central Asia. It is very similar to the closely related house spar ...

s. Paired birds greet by engaging in up-down and head-shaking crouch displays, and clattering the beak while throwing back the head. Pairs copulate frequently throughout the month before eggs are laid. High-frequency pair copulation is usually associated with sperm competition

Sperm competition is the competitive process between spermatozoa of two or more different males to fertilize the same egg during sexual reproduction. Competition can occur when females have multiple potential mating partners. Greater choice and ...

and high frequency of extra-pair copulation

Extra-pair copulation (EPC) is a mating behaviour in monogamous species. Monogamy is the practice of having only one sexual partner at any one time, forming a long-term bond and combining efforts to raise offspring together; mating outside this pai ...

; however, extra-pair copulation is infrequent in white storks.

A white stork pair raises a single brood a year. The female typically lays four eggs

Humans and human ancestors have scavenged and eaten animal eggs for millions of years. Humans in Southeast Asia had domesticated chickens and harvested their eggs for food by 1,500 BCE. The most widely consumed eggs are those of fowl, especial ...

, though clutches

A clutch is a mechanical device that engages and disengages power transmission, especially from a drive shaft to a driven shaft. In the simplest application, clutches connect and disconnect two rotating shafts (drive shafts or line shafts) ...

of one to seven have been recorded. The eggs are white, but often look dirty or yellowish due to a glutin

Gluten is a structural protein naturally found in certain cereal grains. Although "gluten" often only refers to wheat proteins, in medical literature it refers to the combination of prolamin and glutelin proteins naturally occurring in all grain ...

ous covering. They typically measure , and weigh , of which about is shell. Incubation begins as soon as the first egg is laid, so the brood hatches asynchronously, beginning 33 to 34 days later. The first hatchling typically has a competitive edge over the others. While stronger chicks are not aggressive towards weaker siblings, as is the case in some species, weak or small chicks are sometimes killed by their parents. This behaviour occurs in times of food shortage to reduce brood size and hence increase the chance of survival of the remaining nestlings. White stork nestlings do not attack each other, and their parents' method of feeding them (disgorging large amounts of food at once) means that stronger siblings cannot outcompete weaker ones for food directly, hence parental infanticide is an efficient way of reducing brood size. Despite this, this behaviour has not commonly been observed.

The temperature and weather around the time of hatching in spring is important; cool temperatures and wet weather increase chick mortality and reduce breeding success rates. Somewhat unexpectedly, studies have found that later-hatching chicks which successfully reach adulthood produce more chicks than do their earlier-hatching nestmates. The body weight of the chicks increases rapidly in the first few weeks and reaches a plateau of about in 45 days. The length of the beak increases linearly for about 50 days. Young birds are fed with earthworms and insects, which are regurgitated by the parents onto the floor of the nest. Older chicks reach into the mouths of parents to obtain food. Chicks fledge 58 to 64 days after hatching.

White storks generally begin breeding when about four years old, although the age of first breeding has been recorded as early as two years and as late as seven years. The oldest known wild white stork lived for 39 years after being ringed in Switzerland, while captive birds have lived for more than 35 years.

The temperature and weather around the time of hatching in spring is important; cool temperatures and wet weather increase chick mortality and reduce breeding success rates. Somewhat unexpectedly, studies have found that later-hatching chicks which successfully reach adulthood produce more chicks than do their earlier-hatching nestmates. The body weight of the chicks increases rapidly in the first few weeks and reaches a plateau of about in 45 days. The length of the beak increases linearly for about 50 days. Young birds are fed with earthworms and insects, which are regurgitated by the parents onto the floor of the nest. Older chicks reach into the mouths of parents to obtain food. Chicks fledge 58 to 64 days after hatching.

White storks generally begin breeding when about four years old, although the age of first breeding has been recorded as early as two years and as late as seven years. The oldest known wild white stork lived for 39 years after being ringed in Switzerland, while captive birds have lived for more than 35 years.

Feeding

White storks consume a wide variety of animal prey. They prefer to forage in meadows that are within roughly 5 km (3 mi) of their nest and sites where the vegetation is shorter so that their prey is more accessible. Their diet varies according to season, locality and prey availability. Common food items include insects (primarily beetles, grasshoppers, locusts and crickets), earthworms, reptiles, amphibians, particularly frog species such as theedible frog

The edible frog (''Pelophylax'' kl. ''esculentus'') is a species of common European frog, also known as the common water frog or green frog (however, this latter term is also used for the North American species ''Rana clamitans'').

It is used ...

(''Pelophylax'' kl. ''esculentus'') and common frog

The common frog or grass frog (''Rana temporaria''), also known as the European common frog, European common brown frog, European grass frog, European Holarctic true frog, European pond frog or European brown frog, is a semi-aquatic amphibian ...

(''Rana temporaria'') and small mammals such as voles, moles and shrews. Less commonly, they also eat bird eggs and young birds, fish, molluscs, crustaceans and scorpions. They hunt mainly during the day, swallowing small prey whole, but killing and breaking apart larger prey before swallowing. Rubber bands are mistaken for earthworms and consumed, occasionally resulting in fatal blockage of the digestive tract.

Birds returning to Latvia during spring have been shown to locate their prey, moor frogs ('' Rana arvalis''), by homing in on the mating calls produced by aggregations of male frogs.

The diet of non-breeding birds is similar to that of breeding birds, but food items are more often taken from dry areas. White storks wintering in western India have been observed to follow

Birds returning to Latvia during spring have been shown to locate their prey, moor frogs ('' Rana arvalis''), by homing in on the mating calls produced by aggregations of male frogs.

The diet of non-breeding birds is similar to that of breeding birds, but food items are more often taken from dry areas. White storks wintering in western India have been observed to follow blackbuck

The blackbuck (''Antilope cervicapra''), also known as the Indian antelope, is an antelope native to India and Nepal. It inhabits grassy plains and lightly forested areas with perennial water sources.

It stands up to high at the shoulder. Ma ...

to capture insects disturbed by them. Wintering white storks in India sometimes forage along with the woolly-necked stork

The Asian woollyneck and African woollyneck (''Ciconia episcopus'' and ''Ciconia microscelis'') are two species of large wading bird in the stork family Ciconiidae. It breeds singly, or in small loose colonies. It is distributed in a wide varie ...

(''Ciconia episcopus''). Food piracy has been recorded in India with a rodent captured by a western marsh harrier

The western marsh harrier (''Circus aeruginosus'') is a large harrier, a bird of prey from temperate and subtropical western Eurasia and adjacent Africa. It is also known as the Eurasian marsh harrier. Formerly, a number of relatives were includ ...

appropriated by a white stork, while Montagu's harrier

Montagu's harrier (''Circus pygargus'') is a migratory bird of prey of the harrier family. Its common name commemorates the British naturalist George Montagu.

Taxonomy

The first formal description of Montagu's harrier was by the Swedish na ...

is known to harass white storks foraging for voles in some parts of Poland. White storks can exploit landfill sites for food during the breeding season, migration period and winter.

Parasites and diseases

White stork nests arehabitat

In ecology, the term habitat summarises the array of resources, physical and biotic factors that are present in an area, such as to support the survival and reproduction of a particular species. A species habitat can be seen as the physical ...

s for an array of small arthropods, particularly over the warmer months after the birds arrive to breed. Nesting over successive years, the storks bring more material to line their nests and layers of organic material accumulate within them. Not only do their bodies tend to regulate temperatures within the nest, but excrement, food remains and feather and skin fragments provide nourishment for a large and diverse population of free-living mesostigmatic mites. A survey of twelve nests found 13,352 individuals of 34 species, the most common being '' Macrocheles merdarius'', '' M. robustulus'', '' Uroobovella pyriformis'' and '' Trichouropoda orbicularis'', which together represented almost 85% of all the specimens collected. These feed on the eggs and larvae of insects and on nematode

The nematodes ( or grc-gre, Νηματώδη; la, Nematoda) or roundworms constitute the phylum Nematoda (also called Nemathelminthes), with plant-Parasitism, parasitic nematodes also known as eelworms. They are a diverse animal phylum inhab ...

s, which are abundant in the nest litter. These mites are dispersed by coprophilous beetles, often of the family Scarabaeidae

The family Scarabaeidae, as currently defined, consists of over 30,000 species of beetles worldwide; they are often called scarabs or scarab beetles. The classification of this family has undergone significant change in recent years. Several sub ...

, or on dung brought by the storks during nest construction. Parasitic mites do not occur, perhaps being controlled by the predatory species. The overall effect of the mite population is unclear, the mites may have a role in suppressing harmful organisms (and hence be beneficial), or they may themselves have an adverse effect on nestlings.

The birds themselves host species belonging to more than four genera of feather mite

Feather mites are the members of diverse mite superfamilies:

* superorder Acariformes

** Psoroptidia

*** Analgoidea

*** Freyanoidea

*** Pterolichoidea

* superorder Parasitiformes

** Dermanyssoidea

They are ectoparasites on bird

B ...

s. These mites, including '' Freyanopterolichus pelargicus'', and '' Pelargolichus didactylus'' live on fungi growing on the feathers. The fungi found on the plumage may feed on the keratin

Keratin () is one of a family of structural fibrous proteins also known as ''scleroproteins''. Alpha-keratin (α-keratin) is a type of keratin found in vertebrates. It is the key structural material making up scales, hair, nails, feathers, ho ...

of the outer feathers or on feather oil. Chewing lice

The Mallophaga are a possibly paraphyletic section

Section, Sectioning or Sectioned may refer to:

Arts, entertainment and media

* Section (music), a complete, but not independent, musical idea

* Section (typography), a subdivision, especia ...

such as '' Colpocephalum zebra'' tend to be found on the wings, and '' Neophilopterus incompletus'' elsewhere on the body.

The white stork also carries several types of internal parasites, including ''Toxoplasma gondii

''Toxoplasma gondii'' () is an obligate intracellular parasitic protozoan (specifically an apicomplexan) that causes toxoplasmosis. Found worldwide, ''T. gondii'' is capable of infecting virtually all warm-blooded animals, but felids, such as d ...

'' and intestinal parasite

An intestinal parasite infection is a condition in which a parasite infects the gastro-intestinal tract of humans and other animals. Such parasites can live anywhere in the body, but most prefer the intestinal wall.

Routes of exposure and infe ...

s of the genus '' Giardia''. A study of 120 white stork carcasses from Saxony-Anhalt

Saxony-Anhalt (german: Sachsen-Anhalt ; nds, Sassen-Anholt) is a state of Germany, bordering the states of Brandenburg, Saxony, Thuringia and Lower Saxony. It covers an area of

and has a population of 2.18 million inhabitants, making it the ...

and Brandenburg

Brandenburg (; nds, Brannenborg; dsb, Bramborska ) is a states of Germany, state in the northeast of Germany bordering the states of Mecklenburg-Vorpommern, Lower Saxony, Saxony-Anhalt, and Saxony, as well as the country of Poland. With an ar ...

in Germany yielded eight species of trematode

Trematoda is a class of flatworms known as flukes. They are obligate internal parasites with a complex life cycle requiring at least two hosts. The intermediate host, in which asexual reproduction occurs, is usually a snail. The definitive host ...

(fluke), four cestode (tapeworm) species, and at least three species of nematode

The nematodes ( or grc-gre, Νηματώδη; la, Nematoda) or roundworms constitute the phylum Nematoda (also called Nemathelminthes), with plant-Parasitism, parasitic nematodes also known as eelworms. They are a diverse animal phylum inhab ...

. One species of fluke, '' Chaunocephalus ferox'', caused lesions in the wall of the small intestine in a number of birds admitted to two rehabilitation centres in central Spain, and was associated with reduced weight. It is a recognised pathogen and cause of morbidity in the Asian openbill

The Asian openbill or Asian openbill stork (''Anastomus oscitans'') is a large wading bird in the stork family Ciconiidae. This distinctive stork is found mainly in the Indian subcontinent and Southeast Asia. It is greyish or white with glossy ...

(''Anastomus oscitans''). More recently, the thorough study performed by J. Sitko and P. Heneberg in the Czech Republic in 1962–2013 suggested that the central European white storks host 11 helminth species. '' Chaunocephalus ferox'', '' Tylodelphys excavata'' and '' Dictymetra discoidea'' were reported to be the dominant ones. The other species found included '' Cathaemasia hians'', '' Echinochasmus spinulosus'', '' Echinostoma revolutum'', '' Echinostoma sudanense'', '' Duboisia syriaca'', '' Apharyngostrigea cornu'', ''Capillaria

''Capillaria'' ( hu, Capillária, 1921) is a fantasy novel by Hungarian author Frigyes Karinthy, which depicts an undersea world inhabited exclusively by women, recounts, in a satirical vein reminiscent of the style of Jonathan Swift, the firs ...

'' sp. and '' Dictymetra discoidea''. Juvenile white storks were shown to host less species, but the intensity of infection was higher in the juveniles than in the adult storks.

West Nile virus

West Nile virus (WNV) is a single-stranded RNA virus that causes West Nile fever. It is a member of the family '' Flaviviridae'', from the genus '' Flavivirus'', which also contains the Zika virus, dengue virus, and yellow fever virus. The v ...

(WNV) is mainly a bird infection that is transmitted between birds by mosquito